By 2:30 a.m. on March 10, 1945, the bombers had all disappeared over the glowing horizon and the “all clear” sounded across a shattered Tokyo.

While back on Guam, Gen. LeMay and his staffers were breathing a collective sigh of relief, over a million suddenly homeless Japanese wandered the smoldering lunar landscape of their devastated capital city like bewildered phantasms. When the smokey dawn arrived, the grey, muted sunlight revealed badly burned survivors stumbling into what medical centers remained while others returned to ash heaps that were once their neighborhoods searching for family members separated from them in the chaos of the night before. Ishikawa Iwao came upon the charred remains of his wife and two girls. One young girl would recall having to push her way through the dead bodies with her feet. In the Tokyo subway, thousands of naked and seared humanoid figures were piled into the narrow confines. If it was not hell itself, LeMay’s bombers had come as close as the human race could to replicating it on this earth.

Although there were attempts soon after the raid to arrive at a reliable casualty figure, it was guesswork. Many of the Tokyo officials who would have tallied the corpses and presented a body count to the emperor, whose palace had been spared, were either dead, injured, searching for loved ones, or scrounging for food. Various historians, as well as subsequent Japanese and U.S. records, put the death toll at anywhere from 87,000 to over 110,000 with another 40,000 injured. Respected researchers like Edwin Hoyt, however, argued that even the high estimates of fatalities are a gross undercount given the population of the area that was scorched, and that these figures only represent actual counted dead along with approximations based on fragments of clothing, bones, jewelry, and the like. He would actually put the number at over 200,000. We will never know for sure. But what we do know is that, with the possible exception of Hiroshima, the March 9-10, 1945, firebombing of Tokyo was the most lethal single act of war in human history, and certainly tops anything conventional weapons had ever achieved before or since.

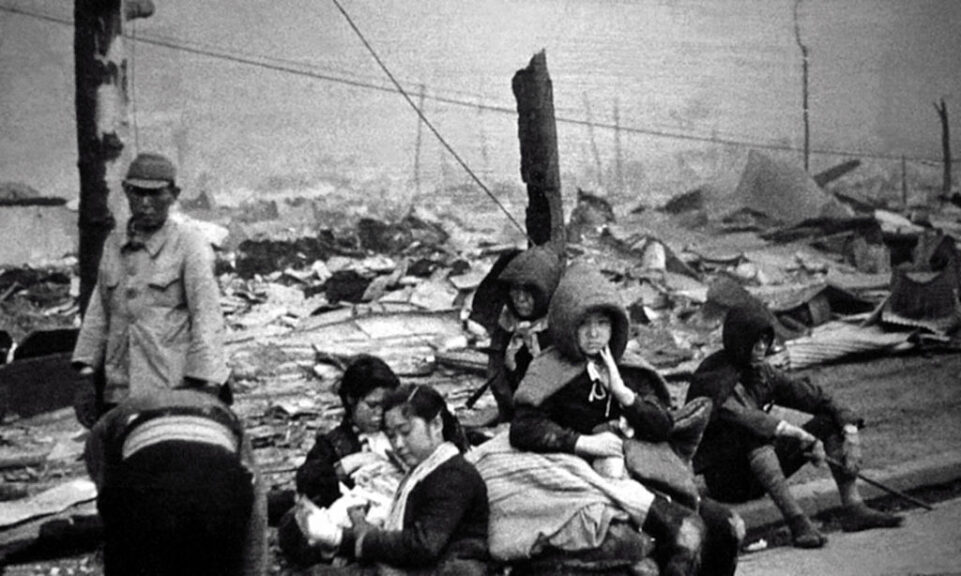

Tokyo residents who lost their homes as a result of the U.S. bombings. 10th March 1945. Photo: Kouyou Ishikawa, officer of the Metropolitan Police Department. Tokyo, Japan. (Photo By Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images)

Despite the mass killing they’d just unleashed, LeMay and his bomber crews were ebullient. Losses hadn’t been 70% as some predicted but rather just 4%: 14 bombers and 96 crewmen lost. This in exchange for reducing over 16 square miles of the enemy’s capital city to ash. The Superfortresses incinerated 63% of the commercial district, wiped out 18% of Tokyo’s industry, and burned to the ground roughly a quarter million buildings and homes, which was 25% of the city.

Flying at low altitude, it turned out, was less taxing on the B-29’s temperamental engines as well as more fuel-efficient. So low-level nighttime fire bombings would be LeMay’s template going forward. In effect, America’s strategy for winning the war was to simply dump burning gasoline over Japan until they finally came to their senses. In fact, over the next six months the B-29s would proceed to burn out one Japanese city after another, including several return trips to embattled Tokyo, effectively hammering a nation already teetering due to critical shortages to its knees. In fact, LeMay was confident that by putting every Japanese city to the torch, his B-29s could compel Japan to surrender without ever having to invade, or drop an atomic bomb. And, as post-war surveys revealed, of all the reasons Japanese civilians believed their nation had no choice but to end the war, the air raids topped the list.

And no wonder. As historian and author James Bradley writes: “Curtis [LeMay] was clearly much more effective than the American bombers had been in Europe. Bombing destroyed seventy-nine square miles of Germany’s urban area. Curtis destroyed more than twice as much urban area in Japan. 178 square miles…In fact, the damage in just two Japanese cities, Tokyo (56.3 square miles) and Osaka (16.4 square miles) nearly equaled all the damage done to all German cities put together.” And these were just two of nearly 70 cities the B-29s burned out between March and August 1945.

Aerial view of Tokyo razed by American bombing carried out on the evening of March 9th by 334 B-29 Super Flying Fortresses. Tokyo, March 1945 (Photo by Mondadori via Getty Images)

Indeed, even after the atomic bombs vaporized Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the firebombing continued; the last Japanese city to be put to the torch was Akita, on August 14, 1945, five days after Nagasaki and just hours before Japan announced its capitulation.

The morality of firebombing or “area bombing” has been a subject of intense debate ever since. Certainly in the modern age where nations like Israel are castigated in the court of global opinion for “disproportionate” responses to acts of war, one is hard-pressed to find proportionality in a bombing campaign that, in ostensible retaliation for 2,400 dead at Pearl Harbor, eventually burned to death over a half million old men, women, and children and rendered over eight million homeless.

To be sure, some in the military did question the ethics of such indiscriminate killing. Brig. Gen. Charles Bonner Feller condemned the Tokyo raid as “one of the most ruthless and barbaric killings of non-combatants in all of history.” LeMay himself candidly conceded, “I suppose if we’d lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminals.”

But when it comes to the bombing of Japan especially, there are two factors to consider before handing down judgement ex post facto. First, 34% of Japanese industrial workers were jammed into her six largest cities. And many of those who did not work on the factory floor were directly involved in contributing to the war effort through the cottage industry of making parts for nearby factories in their home workshops. As one 1944 report to the White House argued, “each factory was like a tree radiating a web of roots throughout the surrounding living areas from which it drew both workers and parts.” In other words, an argument could be made that every Japanese dwelling was a legitimate military target. And thusly, “de-housing”, to use Churchill’s antiseptic phrase, was considered to be justified.

Feller’s rare dissent aside, we are speaking of what the Germans called “terror bombing” and the Japanese “slaughter bombing” with the advantage of decades of hindsight and reflection. Today we know that by March 1945 the war was barely six months away from concluding. But U.S. planners back then certainly could not know this. As far as they were concerned the ferocious battles of Peleliu, Manila, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa amply demonstrated that, if anything, Japanese resistance was stiffening, and growing ever more fanatical. In 1945, Germany may have been on the ropes, but Japan was showing no hint of surrender. The trusted journalist Ernie Pyle wrote, “The closer we get to Japan, the harder it will be. To me it looks like trying days for us in the years ahead.” As Bradley points out, Pyle said years, not months.

It was with this backdrop of frustration with an enemy who, though clearly beaten, still refused to give up, combined with the brutality of the Japanese themselves — especially their sadistic conduct towards civilians and POWs that was well-known by then — that erased any moral qualms from the nation’s collective conscience. The growing consensus both inside the War Department as well as Main Street, USA, was that this madness had to end. And if it took burning all of Japan back into the stone age to stop our boys from coming home in coffins or maimed and mutilated, then so be it. Who are we, basking in the eighth decade of the hard-won Pax Americana, to judge those who saw nothing but a human catastrophe looming before them? As the war inexorably moved towards what would have been its inevitable gory climax, all that lay ahead was an invasion of the home islands with literally millions of Allied, and most likely tens of millions of Japanese, casualties to pay the price.

As for the men who carried out the burning of Tokyo that night, once the euphoria of surviving a mission so many expected to be their last wore off, they no doubt pondered the ethics of dumping napalm on defenseless people below. But training, discipline, and war-weariness had instilled in most of them a sense of clinical detachment. They just wanted to get in, execute the mission, and get out of there in one piece. As LeMay would offer unapologetically, “Every soldier thinks about the moral aspect of what he is doing. But all war is immoral, and if you let that bother you, you’re not a good soldier.”

On August 6, 1945, the uranium bomb “Little Boy” destroyed Hiroshima. Three days later the plutonium bomb “Fat Man” obliterated Nagasaki. But Japan’s most stalwart militarists, who were more than prepared to sacrifice their entire population to thwart an Allied invasion, viewed atomic weapons as more of a gradual rather than quantum leap in escalation. After all, as with the M69, the atomic bombs killed most of their victims with fire.

Russia’s invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria on August 8, 1945, certainly removed another piece of their wobbly Jenga tower. One and a half million Red Army troops attacked the emperor’s three quarter of a million warriors in the Chinese province and, along with vengeful Manchus, engaged in the mass killing, looting, and rape of thousands of Japanese “pioneers,” and sent 700,000 captives to Stalin’s gulags.

Even the intrepid U.S. submariners effectively sinking the Japanese Merchant Marine did not alone end Japan’s war effort. Dai Nippon’s commanders still ate well, drank good sake, and ravished enslaved “comfort women” while their starving people subsisted on grasshoppers and sawdust cakes.

Morality aside, a strong case can be made that, of all the factors that led to Japan’s ultimate surrender, it was the firebombing that weighed most heavily in Hirohito’s decision to compel his nation to “bear the unbearable, and “endure the unendurable.” In fact, it is quite conceivable to imagine eventual U.S. victory over Japan through “slaughter bombing” alone. In a meeting with Gen. Arnold, LeMay informed him that by September 1945 there would be no more Japanese targets left to bomb. “And with the targets gone we couldn’t see much of any war going on.” According to Prince Fumimaro Konoe, “…the thing that brought about the determination to make peace was the prolonged bombing by the B-29.” It makes one wonder if Hiroshima and Nagasaki ever needed to occur. Although others would argue that the atom bombs were, in fact, the essential wake-up call demonstrations of the awesome power arrayed against Japan. In a post-war interview, Prime Minister Suzuki Kantaro stated, “The atom bomb didn’t end the war, but it prompted the emperor to make a decision.” The debate continues.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Again, these are questions revisited today through the clear lens of decades of hindsight. At the time, the U.S. government, seeing no end in sight, had a solemn obligation to the American people to do whatever was necessary to end the costliest war in human history. Still, no matter what ultimately prompted Japan’s leaders to accept defeat, the countdown to that defeat began on a terrible March night over Tokyo, eighty years ago, when the B-29s came in force, and the night sky rained fire. And the hellfire of total war finally came home to Japan.

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities fund manager, author, and columnist whose articles have appeared on the pages of The Daily Wire, The Wall Street Journal, NY Post, NY Daily News, National Review, The Hill, The Federalist, Zerohedge, and other outlets. He is the author of three books. Follow him on Substack and X/Twitter.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.