Mabuni Hill rises 300 feet above the Pacific Ocean that thrashes at the remote island of Okinawa. Situated on the crest is the tree-lined Okinawa Peace Memorial Park. The most moving feature of the park is the Cornerstone of Peace, consisting of 116 concentric arcs of black granite stelae stretching 2,200 feet and into which are etched the names of over 240,000 who died here 80 years ago. They came from countries including Japan, the United States, the UK and British Commonwealth, Korea, and Taiwan. Given the tranquility of this picturesque hilltop, such a memorial seems strangely out of place. And yet, as with so many such locations scattered throughout the Western Pacific, the quietude offers a sharp contrast to the events of stunning violence and brutality it commemorates — the biggest, bloodiest, and in many ways most tragic, battle of the Pacific War.

Yuichi Yamazaki/Getty Images

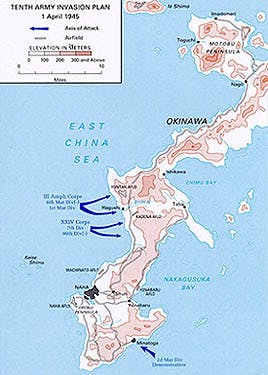

Okinawa is the largest in the Ryukyu island chain and the southernmost of Japan’s 47 prefectures. Located halfway between Japan and Formosa (Taiwan), it stretches north-to-south some 65 miles with a breadth that ranges from five to 25 miles across. The island is bracketed by the Pacific Ocean on the eastern shore and the East China Sea on the west. In the spring of 1945, the landscape consisted of neatly terraced fields of sweet potatoes and sugar cane, pine forests, quaint villages, rugged escarpments, and was home to 450,000 civilians. Other than a few scattered cities like the capital city Naha, with 65,000 residents, most Okinawans lived in small villages, the majority on the southern one-third of the island. Unfortunately for them, this area would also be the scene of some of the most horrific and prolonged combat of the Second World War.

Map of invasion of Okinawa. Wikimedia Commons.

After the Meiji Restoration, Japan annexed the Ryukyus in 1879, effectively ending the seven-century reign of five monarchical dynasties. Smaller and darker than their Nipponese overlords, the native residents were treated as second-class citizens and racial inferiors. The Japanese believed their emperor, Hirohito, to be the 124th descendent of the goddess Amaterasu, and thus were they preordained to rule the world from their divine island chain that fell as drops from a heavenly being’s sword. Like the Chinese, Koreans, Filipinos, and others in Japan’s collapsing “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”, Okinawans were subjected to what Orwell called a “racial theory even more extreme than that of the Germans.”

By March 1945, after nearly three-and-a-half years of bitter fighting, the Pacific War had reached Dai Nippon’s doorstep. The Philippines were in U.S. hands, cutting off Japan’s supply lines to the Dutch East Indies. The island bastion of Iwo Jima was lost despite a tenacious defense. Curtis LeMay’s B-29s had begun a relentless firebombing campaign flying from the recently captured Marianas, while U.S. warships roamed Japan’s waters, firing shells and sending waves of attack planes to wreak havoc on her sacred soil. The emperor’s military chiefs in Tokyo knew that Okinawa was now in the sights of the Americans. Unless they could find some way to repel the enemy in all his might, Japan would be next.

Like many islands that dot the vastness of the Pacific, this ancient land, and the good-natured if stoical people who inhabited it, was a victim of its geography. Situated just 350 miles south of Kyushu, and featuring several airfields and large harbors, Okinawa and its surrounding islands presented the Americans with an ideal forward staging area for the final invasion of the Japanese mainland. After months of planning, at the beginning of 1945, the United States military leviathan, fully mobilized and at the height of its power, was ready to descend upon this idyllic island and its unsuspecting inhabitants.

LSTs and LSMs on an Okinawa beach with a crowd of other amphibious shipping offshore, 3 April 1945. Naval History and Heritage Command.

Steaming into the East China Sea and bearing down on the Ryukyus was the largest combined naval and amphibious force of the Pacific War. Designated Operation Iceberg, in terms of the number of vessels committed and troops deployed, the seizure of the islands rivaled the scope of the Normandy landings ten months earlier. A Japanese scout flying overhead (before being inevitably shot down) and gazing down on the U.S. armada would have beheld a sight to take his breath away. Stretched out to the horizon were over 1,400 vessels of all sizes that made up Rear Adm. Richmond Kelly Turner’s amphibious Task Force (TF) 51 and Rear Adm. William H.P. Blandy’s support TF-52. The ships came from all over the Pacific from ports as far away as Ulithi, Eniwetok, Saipan, Guadalcanal, New Caledonia, Espiritu Santo, Leyte, Oahu and even Seattle 6,000 miles across the Pacific, making this the longest supply line of the war, all converging on this 880-square mile point on the map.

And the dispirited Japanese flier would not have even been able to see the U.S. Fast Carrier TF-58, under the superb leadership of Vice Adm. Marc A. Mitscher, patrolling the waters 60 miles off Okinawa’s eastern shore and sending waves of attack planes to support the impending landings. Mitscher’s “Big Blue Fleet,” as it was called, brought to battle the most powerful naval strike force in the war: 17 carriers and escort carriers fielding over 1,000 aircraft, five fast battleships, 14 cruisers, and 58 destroyers.

As if this wasn’t enough sheer power, for the first time in the war, the Royal Navy’s Pacific Fleet, under the command of Vice Adm. Sir Bernard Rawlings and designated TF-57 for Iceberg, joined their American allies in the Pacific. Rawlings brought with him four carriers (which carried roughly half the number of aircraft as their U.S. counterparts), two battleships, five cruisers, and fifteen destroyers to cover the southern approaches to the island while raiding Japanese bases on Formosa.

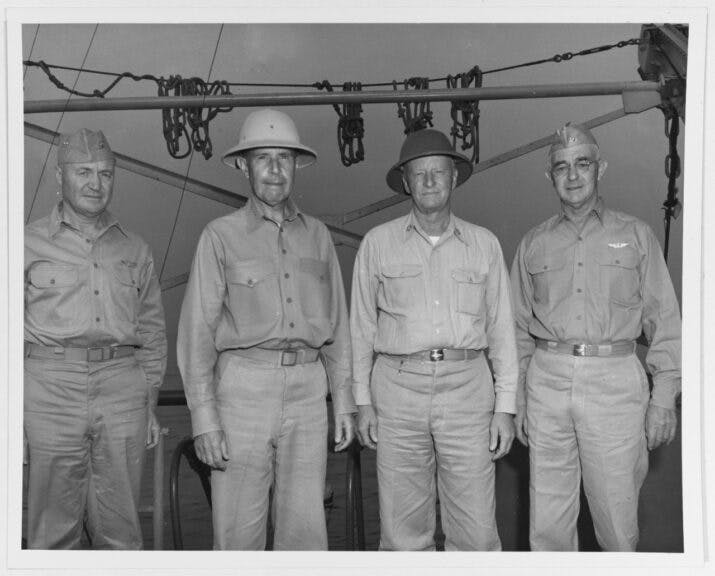

The logistics of such an operation beggars the mind. The combined naval task forces alone, dubbed the Fifth Fleet and under overall command of Adm. Raymond Spruance, would burn more fuel in the three months of Operation Iceberg than Japan imported during all of 1944. The late Admiral Yamamoto’s fears about going to war with such an industrial “sleeping giant” had been realized on a scale he could never have imagined.

Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, USN, Fleet Admiral C.W. Nimitz, USN, and Vice Admiral Richard K. Turner, USN aboard USS ELDORADO (AGC-11) at Okinawa, 1945. NHHC Collection. U.S. Navy.

On March 25, 1945, in a prelude to the main assault on Okinawa, scheduled for April 1, landing teams of the 77th Division stormed and, after three days of fighting, secured several peripheral islands that made up the Kerama Retto and Keisi Shima groups. They’d been serving as bases for some 300 explosives-laden Japanese suicide speed boats as well as float planes. In a grim repeat of the experiences of the Marines on Saipan, the GIs encountered the bloody, mangled bodies of civilians, including women and children. The Japanese had forced the islanders to surrender all their food and then handed the natives two grenades with instructions to throw one at the Americans and use the other on themselves. Marinated in years of vicious propaganda warning them that the American beasts would gleefully rape, dismember, burn, or crush with steamrollers any Okinawan they encountered, hundreds of misguided natives chose mass suicide.

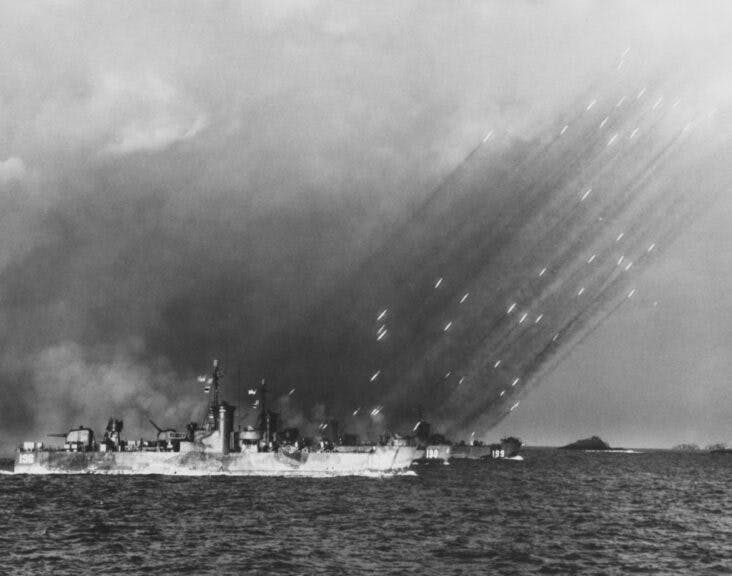

On that same day, in the waters off Okinawa, Vice Adm. Morton Deyo’s Gunfire and Covering Force zeroed in on the Hagushi beaches and the surrounding hills and commenced the preliminary shore bombardment. Like a thousand thunderclaps, the deafening roar of the guns and whooshing shells spinning toward their targets announced that the preliminary shore bombardment had begun. Nine battleships, 10 cruisers, 32 destroyers, and 177 gunboats, along with a dozen landing craft converted to rocket launchers, went to work blasting pre-selected targets and general “softening up” of the landing zone. In seven days leading up to the landings, Deyo’s warships would fire 27,000 shells as well as 33,000 rockets and 22,500 mortar rounds onto the besieged island while petrified Okinawans hastily fled for cover farther inland.

USS LSM(R)-190 (MacKay), a United States Navy LSM(R)-188-class Landing Ship Medium (Rocket), fires a barrage of rockets in salvos on to the shores of Tokishi Shima in a prelanding bombardment during the Okinawa Campaign on 27th March 1945. US Navy Official Photo. (Photo by FPG/Archive Photos/Getty Images).

At precisely 0406 on Easter Sunday, April 1, 1945, designated “L-Day”, Adm. Turner gave the order: “Land the landing force!” The big guns opened up yet again, blasting Hagushi for an hour-and-a-half in a continuation of the pounding the island had been subjected to over the past week while occasionally pausing to allow Mitscher’s carrier planes to drop their payloads. At 0830, to coincide with high tide to clear the coral reef, amphibious landing craft carrying the first elements of the U.S. Tenth Army headed in. The temperature was a pleasant if humid 75 degrees. For troops used to the steaming tropical jungles of previous campaigns, Okinawa’s temperate weather reminded them more of home than some alien land.

USS Tennessee. Bombarding Okinawa with her 14/50 main battery guns, as LVTs in the foreground carry troops to the invasion beaches, 1 April 1945. U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph.

Tenth Army, Iceberg’s ground element, was a combined Army and Marine expeditionary force; its overall commander, Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., was the only son of the Confederate general of the same name. The Marine contingent dubbed III Amphibious Corps and led by USMC Maj. Gen. Roy S. Geiger consisted of the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions, with the 2nd feinting a landing on the south shore of the island to confuse the defenders. The Army’s XXIV Corps, fielding the 7th, 27th, 77th, and 96th Divisions, was under the command of Maj. Gen. John R. Hodge. The Tenth Army numbered a total of 182,000 men, which was a fraction of the 548,000 assigned to Operation Iceberg.

Ferrying 91,000 troops and attendant seamen in the initial assault force, the amphibious vehicles chugged toward the expansive Hagushi beaches in a formation eighteen ranks deep and seven miles across; each vessel flew a colored pennant to announce its designated beach. It was an awesome, even majestic, sight. To Adm. Deyo, the waves of landing craft “possessed something of the color of medieval warfare, advancing relentlessly with their banners flying.” Capt. Samuel Morrison watched the pageantry from the bridge of the battleship Tennessee; he tried to count all the landing vessels but stopped at “the incredible figure of 700.” He added, “No finer spectacle could be seen during the war.” And he’d been at North Africa and Normandy.

Okinawa, Ryukyus Islands, 1945. Amtracs from the US task force coming ashore on L-Day, 1 April 1945. Naval History and Heritage Command.

If the sailors watching from their ships were impressed, the Marines and soldiers hunkered down in either tracked vehicles or LVTs and, heading ever closer to the shoreline, were feeling serious trepidation. Based on the bloodlettings the initial assault waves experienced at Peleliu and Iwo Jima, Iceberg’s planners estimated that the first wave into Hagushi could suffer casualties as high as 80%. The salt-sprayed infantrymen expected to be chewed up by a curtain of steel when they debarked. Many were resigned to the fact that they had only minutes to live.

And yet, when the amtracs pulled up to the beaches and the troops hastily climbed over the sides and rolled onto the sand to take cover, they were met with … nothing.

The beaches were empty and quiet. With the exception of an occasional crack of a rifle here and there, it may as well have been just another practice exercise on friendly shores.

Where were the Japanese?

* * *

Brad Schaeffer is a commodities fund manager, author, and columnist whose articles have appeared on the pages of The Daily Wire, The Wall Street Journal, NY Post, NY Daily News, National Review, The Hill, The Federalist, Zerohedge, and other outlets. He is the author of three books. Follow him on Substack and X/Twitter.

The views expressed in this piece are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The Daily Wire.