CHRIST is risen; yet we die, and suffering remains. With the resurrection, God’s great recreation has begun; yet the cycles of life and death continue. What are we to make of suffering and death after the resurrection? Say too little, and we short-change the resurrection and its greatness. Say too much — or speak too easily — and we risk a glib response to suffering.

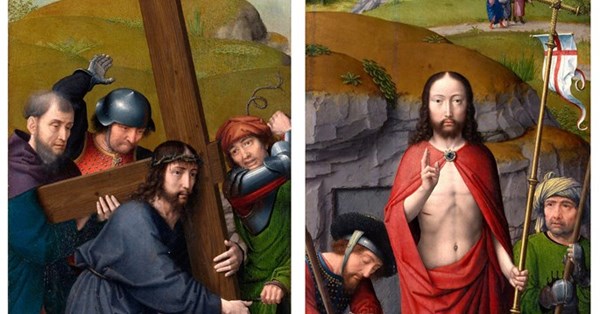

When theologians have tried to understand how the events of Easter transform our experience of suffering, and even of death, two approaches stand out: God’s sharing in our human life; and our sharing in God’s human life. With the first, the emphasis is on God in Christ, sharing our suffering. The other looks at how our experience can then offer a degree of sharing in Christ’s story.

The first approach has been set out poetically, in terms of wayfaring. Going before us in his death and rising, Christ has mapped and secured the territory. The human journey retains its troubles, but it has been charted, its route made safe. As Augustine of Hippo (354-420) put it, “By his humility, Christ has been made a road for us in time, that by his divinity he might be for us a mansion in eternity.”

In St John’s Gospel, Christ says not only that he goes ahead to prepare a dwelling place, but also that he himself is the way to get there (14.2, 6). The remarkable image, in Psalm 23, of God as our shepherd, says something similar: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil: for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff comfort me.”

In the arresting version by St Gregory of Nyssa (c.335-c.394), Christ figures out the “labyrinth” that lies ahead of us: ”Although people get lost wandering in a labyrinth, they can escape its intricate and deceptive turns by meeting someone with experience, and get out by following the footsteps of their leader. So, too, the labyrinth of this life is without exit for human nature, unless someone should take the same way by which he who was in it got outside its confine (the ‘labyrinth’ here being the exitless prison of death).”

ST IRENAEUS (c.130-c.202) wrote in a similar way: “Thus he [Christ] came even to death, that he might be ‘the first-born from the dead, having pre-eminence among all’, the author of life, who goes before all and shows the way.” Christ passed through every stage of life, becoming like us in each, so that we imitate him in whichever stage, including suffering and death, we find ourselves.

With that, Irenaeus offers a pivot between the two approaches introduced above: one emphasising that Christ shared our lot, the other that we can share Christ’s. Irenaeus first teaches that God united himself to suffering and death, sharing in our experience. That also means, however, that we can now, in turn, imitate Christ in his suffering and death.

Several theologians of the Early Church, Irenaeus among them, wrote that “God became what we are so that we can become what God is.” The extraordinary twist is that the God we imitate shared our suffering, in its fullest extremity, in the human nature of Christ. What now happens to us can therefore become an imitation of Christ. As Louis Bouyer (1913-2004) put it, “Our Lord does not need to live on earth again and to die again — this has been done once and for all. But the Church, his body, must progressively, in all her members, pass through everything he did.”

HAVING written a good deal about themes of participation in theology, I now recognise that few of us who focus on that topic have made enough of participation in Christ’s death, given how much New Testament writers dwell upon it (Matthew 16.24; Romans 6.5-11; 7.1-7; 8.17; 2 Corinthians 1.4-7, 3.8-12; Philippians 3.10-11; Colossians. 1.24; 1 Peter. 2.21, 4.13-14. . .). Nor, we might imagine, is the theme preached about often enough — although the Book of Common Prayer holds it before us on Easter Day, no less. The epistle for the day contains the arresting announcement that “you have died,” framed as part of the Good News, since it belongs to the truth that our life is “hidden with Christ in God” (Colossians 3.3).

The principal way in which we share in Christ’s death — “mortification”, as it is sometimes called — is baptism. After baptism, however, this participation also unfolds in the struggles and sufferings of life, as St John Chrysostom (c.347-407) noted: “One is done by Christ in baptism, and the other it is our duty to effect by earnestness afterwards. For that our former sins were buried, came of his gift. But the remaining dead to sin after baptism must be the work of our own earnestness, however much we find God here also giving us large help.”

I am not sure that Chrysostom insists quite enough, here — with his talk of the “work of our own earnestness” — on our total reliance on God; but his analysis is otherwise good. The first great sharing in the paschal mystery comes in baptism. In it, we share Christ’s death as well as his resurrection. There follows a constructive, lifelong sharing in his suffering and death, by which the remaining hold of sin upon us is weakened.

Although this account may be unfamiliar today, it echoes down the centuries, in Protestant as well as Roman Catholic and Orthodox writers. St Paul, so keen to explore our union with Christ in baptism, also wrote magnificently about this subsequent, ongoing process of sharing in Christ’s suffering and death — leading to resurrection — in Philippians 3.

HISTORICALLY, Christians — especially poor and suffering Christians — have seen such sharing in Christ’s agonies as a way to understand and “use” deprivation and illness which has seemed productive and meaningful. Suffering brings them closer to the Christ, the “man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief”. Their suffering can become a self-offering to God, full of hope for resurrection.

There can be problems with that: theological problems, if death and suffering are allowed to eclipse life and resurrection as Christianity’s last word; political or ethical problems, if this outlook stifles protest against an unjust situation (“just offer it up”). Problems, yes; but contemporary theologians should think twice before claiming to know better than those in painful circumstances how to understand their suffering in relation to Christ’s death and rising.

I have offered two angles on the experience of suffering and death after Christ’s resurrection: one, based on God’s making our suffering and death his own; the other, on our fellowship with God in imitation of Christ’s suffering. The foundation is in God’s act, in Christ’s experience, and that is what allows it to be good news. The Easter proclamation is that God’s wayfaring with us in Christ did not get stuck in the grave. If we share in Christ’s suffering, that is so that we can also share in his victory.

The Revd Andrew Davison is Regius Professor of Divinity in the University of Oxford and a Canon Residentiary of Christ Church Cathedral.

Word of the month:

Christology — the branch of Christian theology dealing with Jesus Christ, especially his person and the relation of humanity and divinity; from Greek Christos (“Christ”) and logos (here, “speech about”).