NEVER let it be said, as some have suggested, that modern art and faith have been unable to interrelate. Never let it be said that artists of faith have not been among those leading in modern art’s revolutions.

Dom Sylvester Houédard, a Benedictine priest and theologian based at Prinknash Abbey, was one such, being a leading figure in the development of Concrete Poetry in post-war Britain and the main focus of one half of a fascinating exhibition at the Estorick Collection.

He was not alone, of course. The National Gallery of Ireland, for example, is featuring the work of Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone, both pioneers of modernism in Ireland and artists of faith. The life and work of Houédard is, however, best examined in the contexts of US religious and priests from the 1960s who were artists or poets or both, including Daniel Berrigan, Corita Kent, and Thomas Merton, together with those whom they knew, such as the artist Ad Reinhardt and the poet Robert Lax.

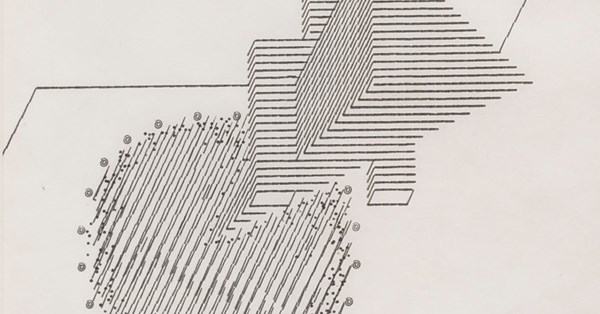

© Lisson Gallery. Courtesy Lisson GalleryDom Sylvester Houédard, condensed aptitude,1971, Typed page

© Lisson Gallery. Courtesy Lisson GalleryDom Sylvester Houédard, condensed aptitude,1971, Typed page

The Estorick Collection is exploring the revolutionary world of experimental poetry by examining the origins of such poetry in Futurism before looking at Houédard’s contribution to Concrete Poetry in Britain. The first half of the exhibition shows work that pre-empts that shown in the second half. While there is generally no direct line of influence, one to the other, the exhibition adds to our fuller understanding of the history of experimental poetry in the same way as exploring the abstract creations of Georgiana Houghton and Hilma af Klint adds to our understanding of the history of abstract art, although their work, which pre-dated the development of the abstract-art movement, did not directly influence that movement.

Italian Futurism was founded and led by a poet — Filippo Tommaso Marinetti — and its many writers reflected the movement’s desire to “redouble the expressive force of words” by emphasising and exploiting the visual and/or sonic dimensions of language. The show, therefore, includes rare original editions of works, including Fortunato Depero’s famous “bolted book” Depero futurista, as well as newspapers and journals such as L’Italia futurista, which made a significant contribution to the dissemination of new poetic research and helped to establish an international avant-garde network.

Then, from the early 1960s onward, Houédard (often known as dsh) wrote extensively on new approaches to creativity, spirituality, and philosophy, while collaborating with figures such as Gustav Metzger, David Medalla, and John Cage. Together with other British exponents of concrete poetry, such as Ian Hamilton Finlay, John Furnival, Edwin Morgan, and Bob Cobbing, whose work is also on display, he helped to shape the development of post-war British poetry, and also influenced the global experimental-poetry movement.

His work, often created using a standard Olivetti Lettera 22 typewriter, blurs the boundaries between literature and visual art. His “typestracts” (a portmanteau word, coined by Morgan, which combines “typewriter” and “abstract”) consist of abstract patterns or shapes formed by typewritten characters. Alongside his typestracts are laminated collages in which text cut from newspapers and magazines relates to coloured shapes, glue, glitter, and dust.

Christopher Adams notes that “the spiralling forms and abstract motifs characteristic of his work can be seen as attempts to express the ineffable, or to represent spiritual experiences that were unable to be fully articulated by more conventional means.” As such, “his compositions, therefore, contain pronounced philosophical dimensions, as they explore themes of transcendence, contemplation and the relationship between the material and the divine.”

Houédard wrote that “concrete fractures linguistics, atomises words into incoherence, constricting language to jewel-like semantic areas where poet & reader meet in maximum communication with minimum words”. This aim of his work was synonymous with his theological emphasis on becoming. In a sermon, he taught that “all we who live & grow & are conscious can say is ‘I become, I change, I grow.’”

Those others who helped to make Britain an important centre for the theory and practice of concrete poetry and whose work is included here, explored the movement’s principles in their own distinctive ways in works that, as Adams notes, “often placed a greater emphasis on semantics than Houédard’s enigmatic verbo-visual constructions”.

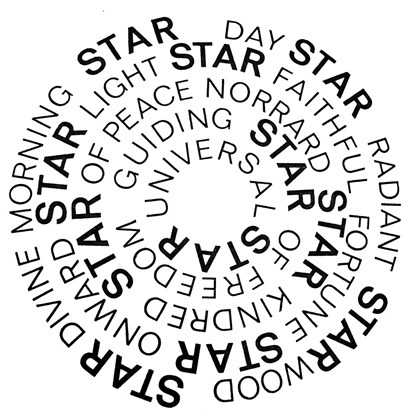

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Sea-Poppy 2 (1968)

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Sea-Poppy 2 (1968)

Of particular note are Hamilton Finlay’s “Sea-Poppy 2”, a circular flower formed (mainly) of religious references to stars, and Morgan’s “Message Clear”, an emergent poem in which text from John 11 is repeated in a variety of fractured and fragmented forms before coalescing in the final clear line as “I am the resurrection and the life”. This emergent poem is one of six. The other five are based on texts taken from Brecht, Burns, Dante, Rimbaud, and The Communist Manifesto.

On Eugen Gomringer’s poem “silencio”, Gabriel Rosenstock writes: “The concrete poem asks the same thing of the reader as does the haiku — to complete it. Fill in the silence. With our own silence.” That sense of a both/and which senses a beyond outside of paradox is central to these works and to Houédard’s spirituality: a sense, as Nicola Simpson has stated, “of a communication between the inner and outer worlds, heaven and earth connected through this kind of tantric staircase, or Jacob’s ladder”.

“Breaking Lines” is at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art, 39A Canonbury Square, London N1, until 11 May. Phone 020 7704 9522. www.estorickcollection.com