NEARLY 50 years ago, and in my late twenties, I was working for the Christian charity Scripture Union as a producer in their Sound and Vision Unit. The job of our small team was to find new ways of communicating the faith with young people. In those days, audio cassettes were all the rage, and we were thinking about how we could use them to get the message into the hands and hearts of the next generation.

We found a brilliant book by the children’s writer Jenny Robertson retelling the gospel story, which we put on to cassette with colouring-in cards, in a series called Colour In As You Listen. We invited well-known performers of the day, such as Dora Bryan, Dame Thora Hird, Derek Nimmo, and Kenneth Williams, to record them — and they all said “Yes.”

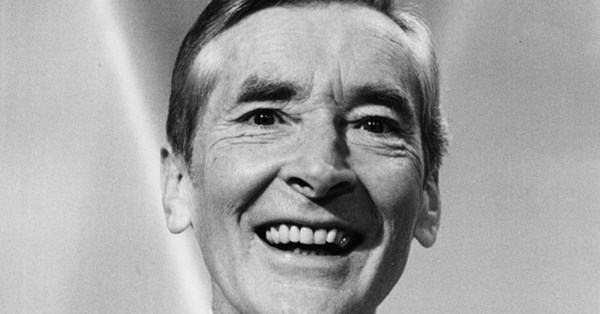

Wes Butters, in his biography of Kenneth, writes about how there were small corners of his life that his many friends knew little about. His faith was one of them. I recorded Kenneth (“Mr Williams” to me, then) telling the story of Jesus’s baptism, his temptations in the wilderness, and the parables of the Good Samaritan, the Prodigal Son, the Buried Treasure, and the Pearl of Great Price.

I’ve kept these recordings for more than 40 years. They have never before been broadcast. But that will change from the eve of Holy Week, when they feature in a BBC Radio 4 programme, Archive on 4: Said the Actor to the Bishop.

The programme explores Kenneth’s faith, his life, and his death. Contributors include those who knew him, and those such as the Children’s Laureate, Frank Cottrell-Boyce, and the Dean of Southwark, the Very Revd Dr Mark Oakley, who react as they listen to his rendition for the first time. The Dean, when he was a student, got to know Kenneth and formed a friendship with him shortly before he died.

They talk about Kenneth’s artistry as a storyteller, which children loved largely through his many performances on Jackanory. He and Bernard Cribbins vied with each other for top billing, and the latter just pipped him to the post for the most appearances on that popular programme. Jeremy Swan, the director, and Anna Hume, the one-time head of Children’s Programmes, explore his enduring appeal to children.

THE first recording I did with him was of the Parable of the Prodigal Son — or, as Jesus told it, the story of the Father and the Two Sons, implying that there might be at least three points to the allegory.

After the first take, I asked if we might do a second. I was a young producer, and simply wanted to cover myself in case I had missed anything in the recording. Indignantly, Kenneth protested, “Why? What was wrong with that one?” “Nothing,” I spluttered. “It was perfect. I just . . .” “Then let’s do the next one!” And it was perfect.

In this, as in the Parable of the Good Samaritan, he used the full range of his repertoire of voices to bring all the characters alive, ranging from a basso profundo to a high pitch, via flaring nostrils and nasal indignation, the rhythm changing from pizzicato diction to the gentle legato of the narrator.

Kenneth knew something that Jesus clearly knew: the power of good storytelling. One evening, I was in the studio editing the parable of the Father and Two Sons, standing over the great Studer recording machine with my razor blade, ready to splice the tape, turning the reels back and forward. When I had finished, I turned around to find a friend standing behind me with tears streaming from his eyes.

“What’s wrong?” I asked. “I’ve just seen myself. I’m that elder brother,” he replied. I have no idea what it was in the elder brother’s demeanour that Kenneth portrayed that spoke to my friend, but it exemplifies the power of storytelling. We lose ourselves in the well-told story, only then to find ourselves.

One of the important discoveries I made in understanding the theological power of stories was reading the original version of the famous verse that includes the words “Now we see through a glass darkly.” There is no “darkly” in the Greek. Literally St Paul wrote that now we see through the glass “in enigmas”. In other words, we do not have the language of heaven to convey truth. We have only enigmas, stories, parables, allegories, similes, and metaphors.

Our predilection for abstract concepts is challenged by the realisation that the abstract concept “God is love” occurs only twice in the whole of the Bible. Never on the lips of Jesus. Never in the Gospels. Never in the Old Testament. Only twice in the letters of John. But, of course, the Bible is full of stories about how God loves us and sometimes in the most surprising ways.

It is that element of surprise that Kenneth captures so beautifully in both the Parables of the Good Samaritan and the Father and Two Sons.

In fact, one theologian has suggested that if you want to discover where to dig for the meaning of a parable, simply tell the story up until the point when you would say, “Surprise, surprise!”

When I asked Anna Hume what one word summed up her memory of Kenneth, she said, without much thought, “Laughter.” I was carpeted for using Kenneth, as my bosses feared the reaction of those who would be offended by his involvement with the Carry On films and their bawdy humour. But it seemed to me that to use a comic actor captured the humour and the humanity of the stories that Jesus told.

ALTHOUGH Kenneth had a faith, he was sceptical and critical of the Church. In between recordings, we talked about his faith. He confessed that he found going to church difficult. As an actor and comedian, he always wanted to entertain people. He found them a distraction to worship. People got in the way of God. He needed to escape them, and to be alone in order to pray, which he did at the end of each day, when he would regularly seek forgiveness for his sins.

He had many friends, although he wasn’t always an easy companion. He could be rude and crude. Dame Maggie Smith, Stanley Baxter, and Gordon Jackson were some of those closest to him. Famously, he would go on holiday with Joe Orton and his lover, although drew the line at some of their hedonistic excesses. He was gay, but for various psychological reasons would never allow himself into a full physical relationship. In many ways, he was a tortured soul, a depressive, who talked and wrote often about suicide.

He lacked the formal education of a university, but was widely read and self-educated. He loved discussing philosophy and theology. I think that that is what made him tick, more than the funny stories that people remember him for as a raconteur.

To thank him for doing the recordings, I gave him two books: Archbishop Michael Ramsey’s To Be a Pilgrim, and Professor J. I. Packer’s Knowing God. A few years later, I did a charity event with him. Then, one day, I was on the top deck of a bus going down the Edgware Road, when I looked down and saw Kenneth getting off. I thought for a moment about jumping off and greeting him. I wish I had. A few weeks later, he was dead. Like many of his fans, I felt devastated.

Whatever the cause of his death, it is one of the ironies of life that, for all the heaviness that weighed down his soul, he breathed laughter and life into the souls of millions.

The Rt Revd James Jones is the author of Justice for Christ’s Sake and With My Whole Heart. Archive on 4: Said the Actor to the Bishop will be broadcast on Radio 4 on 12 April at 8 p.m., and available on BBC Sounds.