Daily Express celebrates it’s 125th anniversary

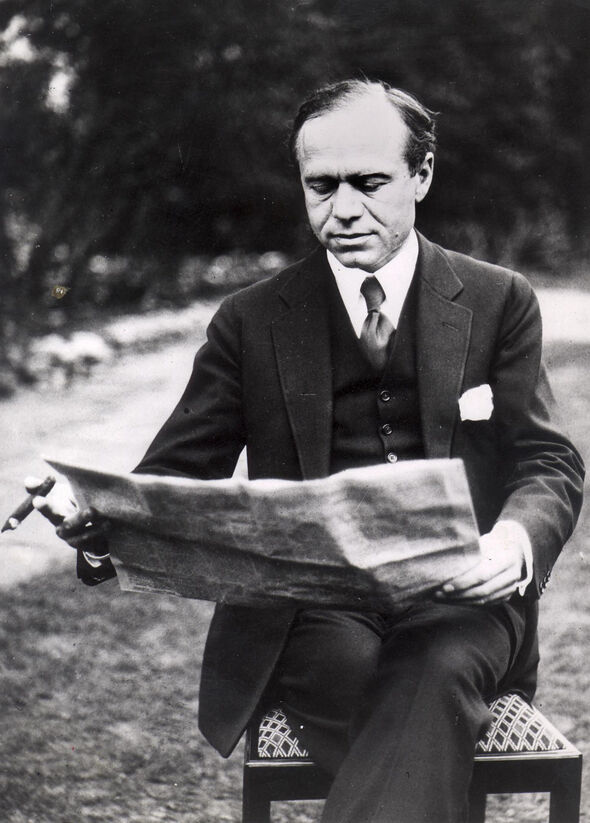

Lord Beaverbrook, owner of Express Newspapers, circa 1935 (Image: Mirrorpix via Getty Images)

If there is one word that perfectly encapsulates Lord Beaverbrook it is mischief.

The Canadian-British newspaper magnate and wartime minister built the Daily Express into the most successful mass-circulation newspaper in the world with sales of 2.25 million copies a day across Britain.

He used it to pursue personal campaigns, most notably for tariff reform and for the British Empire to become a free trade bloc.

So the history-defining Brexit vote is one William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook, would have particularly enjoyed.

Not only because he loathed the idea of Britain joining the Common Market [before we did in 1973] but because he loved stirring things up.

Born in Ontario Lord Beaverbrook died in 1964 aged 85.

But had he been alive 52 years later to witness the stunning referendum result on June 23, 2016, a full century after he took control of the Express, he would have wholeheartedly approved of the most successful newspaper campaign in history.

His great nephew, former Tory MP turned Church of England priest Jonathan Aitken, 82, is the only relative able to remember meeting the “great man”.

He was just 19 when he was summoned to Cherkley Court, Lord Beaverbrook’s sprawling country pile in Surrey, and where he lavishly entertained. The meeting left an indelible mark.

Rev Aitken said: “The first question Uncle Max asked, cackling, was; ‘Are you the sort of boy who likes to stir up mischief? I was a mischief-maker when I was your age. I still am!”

“Then he asked me: ‘Are you for or against the Common Market?’

I replied: “I’m against it sir.”

He said: “Good boy!”

William Maxwell Aitken, 1st Baron Beaverbrook owner of the Sunday and Daily Express (Image: Getty Images)

It was at that initial meeting over Sunday lunch in 1962, a belated invitation because of a long-running family feud, that sparked a lifelong fascination with a man who became a millionaire by the age of 30 but left nothing in his will to his young relative.

Rev Aitken said: “He was small in height, no more than 5’6″ tall, with a stooping gait which made him look tired and shrunken. He had a high, balding forehead whose wizened skin gave him the appearance of a shrivelled prune. “Somehow I had expected, even at 82, to meet a figure who radiated power. However, his physical frailty was deceptive. For the energy of Beaverbrook became apparent when he opened his oversized mouth and began speaking in a rasping transatlantic twang.

‘Aha, the rising generation, he said, creasing his features into an impish grin. And you’re better looking than that father of yours.

‘You’ve gone to university I hear. Where are you studying?’

’I’ve just started at Oxford sir, ‘I replied. I’m reading law at Christ Church.’

‘Oxford, hmmmm, he said with a note of disdain in his voice. ‘I got my education from the university of hard knocks.’

Speaking at his home in central London where he lives alone after the death of his second wife Elizabeth Rees-Williams, Rev Aitken, 82, said: “I remember a crackling sense of humour and a very raucous Canadian voice. He was a troublemaker, mischief maker, and he loved stirring things up.

“He was a firecracker of fun and anti-establishment and that’s why he would have loved the Brexit campaign. He used to say the Daily Express was the working man’s paper – and what he meant was it is always on the side of better conditions and crusading for a fairer society.

“He would be disappointed our horizons had shrunk. He always thought globally, was always interested in Britain’s influence, and was a free-enterprise businessman. He would have thought Britain had lost some of its merchant adventure spirit. And he would certainly be appalled by how much bureaucracy there is now.”

Rev Aitken refers to the newspaper magnate as ‘the great man’ and says he was ‘full of mischief’ (Image: Jonathan Buckmaster )

After taking control of the Express in 1916 Lord Beaverbrook turned the newspaper into a glittering and witty journal with an optimistic attitude. And it became his all-consuming mistress until his death.

Rev Aitken recalled: “Even in his eighties, when I knew him well, Uncle Max was a firecracker of energy, journalistic crusading, political intrigue and boisterous trouble-stirring. He loved dramas. He used the fortune he made as a financier to enjoy life to the full – deal-making, art-collecting, party-giving and wooing many mistresses. But when it came to his own newspapers and to politics, he was un homme serieux [serious man].”

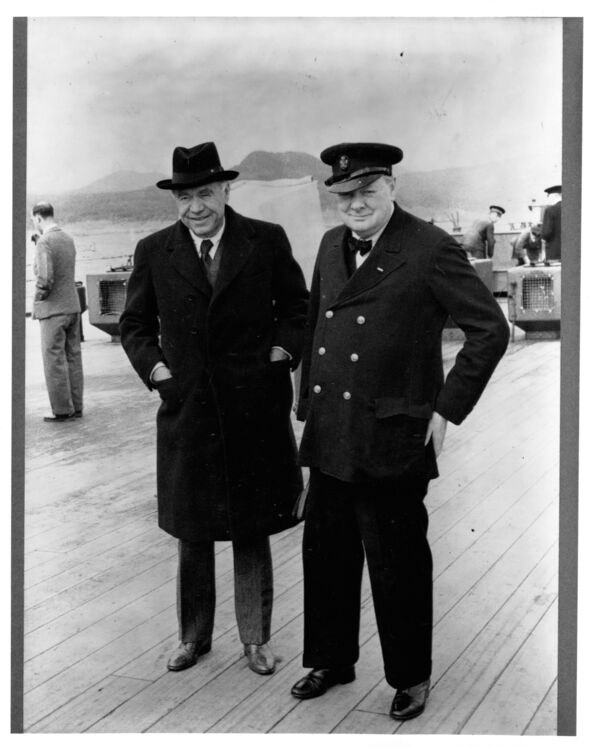

Lord Beaverbrook was variously Winston Churchill’s closest friend and occasional rival.

The pair were the only two politicians to serve in the War Cabinets of both World Wars.

The backstage politician used the Express, the largest circulation newspaper in the world, to appeal to the conservative working class with intensely patriotic news and editorials. And during the Second World War he played a critical role in the war effort, mobilising industrial resources as Winston Churchill’s Minister of Aircraft Production.

Yet despite his breathless accomplishments he fretted he would be remembered only for his books and the world would overlook his achievements as a politician, raconteur and newspaper magnate.

So it is fitting that Brexit could perhaps be described as his – and this newspaper’s greatest legacy. It was a victory won by the Express which crusaded as a lone voice long before others jumped aboard the bandwagon. And it was a campaign waged in the spirit of Lord Beaverbrook, fighting officialdom and the establishment.

Churchill made Lord Beaverbrook Minister of Aircraft Production during the Second World War (Image: Corbis/VCG via Getty Images)

Rev Aitken said: “The last time I saw my great uncle was on his 85th birthday. This was celebrated by a spectacular party given in his honour by Lord Thompson of Fleet, the owner of Times Newspapers, on the night of May 25, 1964.

“There had been considerable doubt prior to the event as to whether the guest of honour would ever make it, for his health was failing badly during the weeks before. He was bedridden for all but a few hours each day, slipping in and out of consciousness. Realising that he might be too ill to attend his own festivities, he tape recorded a speech to be played to the guests at the Dorchester in his absence. It was a pale shadow of the address he eventually delivered in person.

“The reserves of willpower that Uncle Max drew upon to rise from his sick bed and attend the dinner must have been enormous. But when he got to his feet to respond to the toasts, power and energy surged into his voice. He delivered a tour de force of a speech with captivating charm and coruscating wit.

‘All my life I have been an apprentice’, he began, as he thundered down the memory lanes of his careers in business, politics, authorship and journalism, with jokes, teases and flashes of zest.

“Those of us who knew how close he had been to death’s door in the days running up to his birthday, the vigour of his 20-minute speech seemed little short of miraculous. But then came a poignant peroration.

‘Well, now I am in the first day of my eighty-sixth year. I do not feel very different from my eighty-fifth year. But this is my final word. It is time for me to become an apprentice once more. I have not settled in which direction. But somewhere, sometime soon.’

“Many people in the 650-strong audience, including me, were close to tears. But we hid our feelings by singing For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow, followed by Land of Hope and Glory. On the way out I was one of the multitude who congratulated the guest of honour on his speech. As I shook my great-uncle’s hand he asked me to wait on one side for a moment. Ostensibly this was to take part in a family photograph, followed by the agreeable tradition he had invented of giving presents to his relatives on his own birthday. As we all knew it would be the last such occasion, there was a sad and valedictory atmosphere in the room. Yet, when he handed me an envelope containing a handsome cheque, his voice was as strong and cheerful as it had been in his speech.

‘Don’t go off again to that bookmaker of yours with this, will ya?’ he chuckled. ‘For there’s no gambling like a career in politics. Are you still sure that’s what you want to do with your life?’

“Yes — definitely, I replied. Well as I’ve told ya before, politics is the best of lives and the worst of lives. But enjoy it, and make sure you stir up lots of mischief?”

“Thirteen days later he died. I cherish his memory.”

Rev Aitken was elected to Parliament in 1974 (serving until 1997) and was a member of the cabinet during John Major’s premiership. But after being accused of misdeeds in government capacity and suing for libel he was found to have committed perjury during his trial. In 1999 he was sentenced to 18 months in prison, of which he served seven months.

Following his imprisonment, he became a Christian and was ordained as an Anglican priest and prison chaplain.

He said: “Perhaps I may have followed his last words of advice rather too well.

“Yet without the influence of my Uncle Max I would have had a far duller, narrower life. He remains one of my greatest heroes.

“And still now I can hear a familiar Canadian accent, booming out at me: ‘Didn’t I tell ya, we sure stirred up some mischief’.”

Rev Aitken at St Paul’s Cathedral in London in 2018 (Image: PA)